Wireless Hill Future – Part 3 of 6

Before the advent of television, radio reigned supreme. Rather than have scenes depicted visually, the listener had to imagine the activity being enacted. This enabled the mind to conjure up wonderful imagery which was masterfully assisted by the high quality of drama presentation, with actors voices, mood music and incredible sound effects.

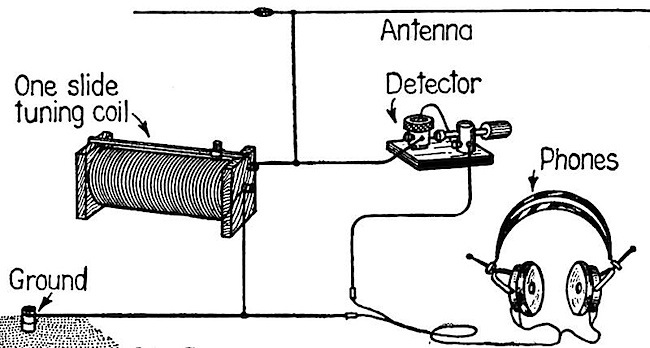

For youngsters wishing to follow their favourite serial in bed, without disturbing their sleeping family, it was popular to employ the simple crystal set and headphones to listen discretely whilst cuddled up in bed. This was technology an enthused child could make, as there were very few components, though it did require an aerial and an earth. An insulated wire out the bedroom window to a tree or the garage and a wire attached to the nearest water pipe sufficed for this purpose.

It was also the earliest wireless receiving technology for those who could not afford a receiver with an amplifier and horn or loudspeaker.

The Wireless Hill Telecommunication Museum had a wonderful array of vintage radio receivers on display and memorabilia from the broadcasting stations all exhibitted in a colourful environment with samples of the music playing from the different eras.

The first wireless transmitters were only capable of broadcasting Morse code, not voice, so radio receivers could be very simple, and tone quality didn’t matter. Then in the 1920s, radio for public consumption was introduced with speech and music broadcasts.

1922 circuit of a simple Crystal Set Radio Tuning was achieved by adjusting either a tuning coil and/or a capacitor connected together to select different stations.

Radio amateurs were the first broadcasters in Australia. Then in the 1920s, the commercial broadcasts began, using voice and music, which gradually became popular as more of the general public acquired receiving sets. At first the broadcasts were limited to the amplitude modulated (AM) frequencies, which meant tuners could be very simple.

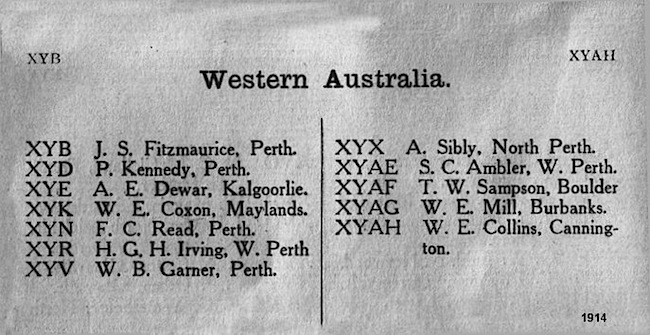

Beginning mid-1910 the PMG Department issued the experimental stations with 2 letter call signs prefixed by “X” for experimental, with no distinction between states, or between private and commercial operators. For example, XAA was J.Y. Nelson the Senior Electrical Engineer of the Sydney PMG Department and also the Sydney radio inspector.

1914 Wireless Institute of Australia call book

When the government wireless stations at Sydney (NSW) and Applecross (WA) commenced operations in 1912 they were initially allocated call-signs POS, for Post Office Sydney, and POP for Post Office Perth,

Then the same year, many British Commonwealth countries adopted the callsign prefix letter V in commemoration of the death of Queen Victoria (22 January 1901). Thus as a result of the international wireless convention, the PO was changed to a VI, hence POS became VIS (Sydney) and POP became VIP (Perth). The government established 22 coastal stations all with VI prefixes.

In mid 1914 the call-signs were altered with a number to identify the state, then 2 letters.

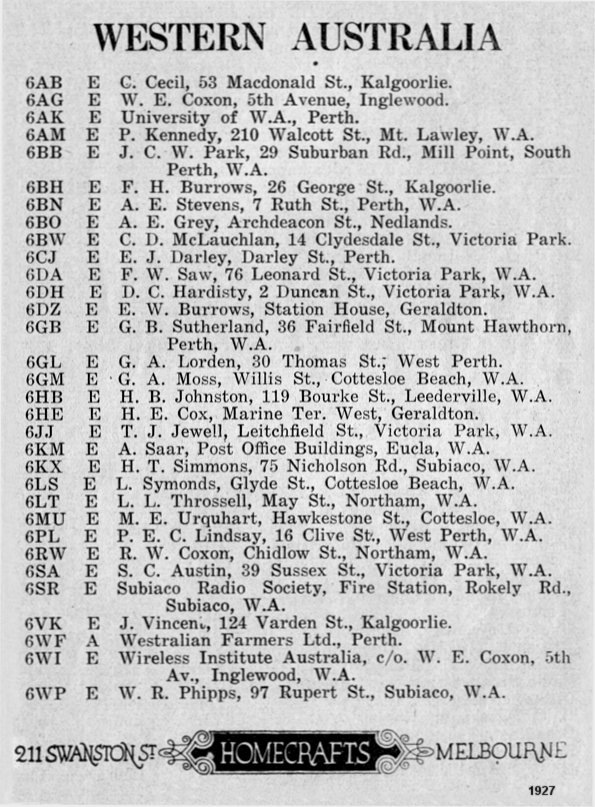

1927 Wireless Institute of Australia call book 6WF was an A Class station and the E represented Experimental – later called an Amateur Station Licence

In 1912, Australia was allocated the call-sign prefix group VH to VK, but these prefixes were not assigned to radio amateurs until 1927.

The Amateur radio fraternity (also called ham radio) engage in the non-commercial exchange of messages, wireless experimentation, training, and emergency communication as a recreational activity, though many of this community also carry their interest over into industry, and have been important pioneers in this field. Wally Coxon (VK6AG) became chief engineer and manager of 6WF, Willy Phipps (VK6WP) became the chief engineer of Whitford’s Broadcasting Network and Harry Simmons (VK6KX) became the chief engineer of West Australian Broadcasters. As 6ML and 6IX broadcast out of the same building, Harry Simmons was the chief engineer of both. Wally Coxon later became the station manager and supervising engineer of 6AM in Northam.

Before the establishment of Radio station 6WF in 1924, the amateur community was permitted to broadcast news and music using their call sign 6BN, registered to A.E. Stevens, for the Subiaco Radio Society. Once regular broadcasting commenced amateurs were no longer permitted to broadcast, although some continued to do so for several years. Willy Phipps used to broadcast a weekly program he called ‘6WP, The Happiness Station’ before becoming the chief engineer of the Whitford’s Broadcasting Network. He also owned a shop at 434 Albany Highway, Victoria Park. It was initially radio and electrical, but later embraced the sale of early television receivers, and was popular as a shop window vantage point during TVW’s test transmissions and opening in 1959.

Pioneering Radio Receiver designed and built in Western Australia

The legendary Wally Coxon (VK6AG), was the most influential radio engineer at the dawn of broadcasting in Western Australia. He became chief engineer and manager of 6WF, Perth’s first radio station, building the transmitter and designing, assembling and testing the early Mulgaphone wireless receivers which first enabled the public state wide to enjoy this new means of entertainment. Wally later became the station manager and supervising engineer of 6AM in Northam.

Early domestic radio consoles were tuned radio frequency receivers and often battery driven for rural use

A typical early three stage tuned radio frequency receiver includes a radio frequency stage, a detector stage and an audio stage. They tended to be more difficult to operate than the more costly and sophisticated Superheterodyne receiver, which converts a received signal to a fixed intermediate frequency, that can then be more conveniently processed than the original radio carrier frequency. By the mid-1930s, commercial production of tuned radio frequency receivers was largely replaced by superheterodyne receivers and virtually all modern radio and television receivers now use the superheterodyne principle.

Early receivers came in all shapes and sizes

(Photo taken by the author at the Wireless Hill Telecommunications Museum)

AWA Radiola receivers were displayed by Wyper Howard Limited at the 1934 Perth Radio Show in the Government House Ballroom

Vendors at the 1934 Radio and Electrical Exhibition included Boans, Nicholson’s, Thompson’s Limited (Beall Radio), Radio Corporation Pty Ltd (Astor), British General Electric Co Ltd (Sylvania Valves, Osram, Magnet and Genalex), MJ Bateman (STC Radio), Wyper Howard Ltd (Radiolla) and the Broadcaster magazine.

Workers at AWA’s Ashfield, NSW factory in 1936

Amalgamated Wireless Australasia Limited (AWA) was Australia’s largest and most prominent electronics organisation undertaking development, manufacture and distribution of radio, telecommunications, television and audio equipment throughout most of the 20th century. They also build and operated transmitters that were employed at the Applecross Wireless Station.

An excellent range of radio receivers were displayed at the Wireless Hill Telecommunications Museum, from the basic crystal set to the first simple triode valve sets, which required headphones for listening. Eventually more powerful receivers were built using a primitive horn, then the loudspeaker was introduced enabling groups to listen simultaneously.

Early Loudspeaker Designs

Astor receivers also made an appearance at the 1934 Perth Radio Show on display at the Radio Corporation Pty Ltd stand

Radio Corporation of Australia Ltd (not to be confused with Radio Corporation of America RCA) was formed in 1926 when three small component manufacturers combined. They commenced to manufacture Astor brand radios the same year. They soon merged with Louis Cohen Wireless Pty Ltd and became Radio Corporation Pty Ltd. The Astor Mickey Mouse series of radios were the most famous radios made by Astor and became one of the biggest selling radios in Australia, with a factory in Victoria. Astor was progressive by offering radios in varying colours compared to other companies that offered the standard wood stains. There was a conflict with Walt Disney for naming one of their radios the Mickey Mouse, and were forced by legal action to stop using the Mickey Mouse logo. In 1939 they became Electronic Industries Ltd when they merged with Eclipse Radio Pty Ltd. By 1940 the factory in Victoria occupied about 8000 square meters and employed 1200. Electronic Industries Ltd was taken over by the giant Philips company in the late 1960s.

Pye Electronics equipment in Australia was also manufactured by Radio Corp between 1950 and 1954 after an association formed during the war between Pye Ltd. of Cambridge, UK and Electronic Industries Ltd. in Australia.

Art deco was not only an architectural influence which began in Paris in the 1920s, but also became fashionable with radio cabinet design and flourished throughout the 1930s, and into the World War II era.

(Photo taken by the author at the Wireless Hill Telecommunications Museum)

A number of early radio receivers were the first items to be removed from the museum building.

Mantle radios with a bakelite casing also began appearing in the 1930s

Bakelite was an early form of brittle plastic, typically dark brown though later to come in many colours. It was made from formaldehyde and phenol, and became popular for electrical equipment and in particular the smaller mantle radios, which most homes could afford.

With the advent of television in the mid and late 1950s, the need to employ the imagination to visualise events was soon replaced by actual vision and sound. Drama, variety programs and quiz shows seemed so much more interesting when one could see things happening, though there were some disappointments with the occasional lack lustre TV productions, which appeared very ordinary compared to listener expectations after their rampant imagination had been let loose with radio, or the small screen black and white image was not as brilliant as the CinemaScope and Technicolor epics, which the movie industry used to counter the competition that television provided.

Wireless Hill Future – in six parts

- Wireless Hill Future – Part 1 of 6

- Wireless Hill Future – Part 2 of 6

- Wireless Hill Future – Part 3 of 6

- Wireless Hill Future – Part 4 of 6

- Wireless Hill Future – Part 5 of 6

- Wireless Hill Future – Part 6 of 6