DOUGLAS JOSEPH BURTON

By Jan Burton Jackson

Among the lifetime collection of photographs, negatives, documents and writings of the late photojournalist Douglas Joseph Burton is a piece of ageing copy paper on which he long ago typed:

“The eye of the camera records all that is true, from the first visible beginnings of life, from the atom to the powerful constellation in outer spaces, and enables man to see what would otherwise be concealed from him.”

The truth of his life’s work in one sentence.

They were the words of the eminent British arts administrator and art historian, Sir John Rothenstein. Doug read, reflected upon and borrowed them in the 1960s, years into his own celebrated career; certainly long after headmaster Tommy Chandler leaned out of his office window at Perth Boys’ School and asked a group of lads playing cricket in the playground if anyone was interested in a job at The West Australian, the local Perth morning newspaper. Most of the boys, in their third year of secondary school, had recently sat the Junior Certificate examinations and were awaiting their fate. It was November 1934. The Great Depression lingered. Most boys of 15 would soon be getting a job. A few lucky ones would be able to stay at school.

Doug Burton, the second youngest of six children of a North Perth widow, was destined for the workforce, and as far as his mother was concerned, preferably in a long and secure career in a bank or the civil service – like his older brothers.

But Tommy Chandler’s news sparked Doug’s interest. He was an intelligent youth, a well-made athlete, curious about what was in the offing and despite family aspirations held a quiet ambition to be a sports journalist. There quickly came the interview at the newspaper offices with a man with the memorable name of Bill Shakespeare, followed by a telephone call to his mother that evening. Suddenly he had the job as an office boy on the editorial floor of the weekend publication, The Western Mail.

Some months later he was offered a position as a cadet photographer, ending his dream of a career as a sports writer, but coming at a critical time in newspaper publication when the narrative power of a photograph was gaining recognition as a pivotal part of news gathering. Barely a decade earlier most newspapers were printed with endless slabs of type relieved occasionally by a line drawing.

Doug took his first photograph in 1935. This was the era of cumbersome cameras, magazine film, flash bulbs, chemicals and dark rooms, when a capable photographer had to know the science and mechanics of the camera and picture making, when the fractional moment captured by the photograph was the result of careful control of the delicate implement that was his tool of trade.

Photography seemed to come naturally and he settled quickly and happily into the newspaper culture. But barely had he begun to make his mark when Hitler invaded Poland. In the New Year of 1940 he joined the militia force of the 10th Light Horse Regiment, proud to call himself Trooper Burton. But after 307 days Doug sought a discharge to enlist in the Royal Australian Air Force, a decision that would foster his instinctive leadership abilities and open up a world that brought him excitement and companionship to his last days.

And he learnt to fly, a skill that would in post-war years enable him to push the boundaries of newsgathering, making inaccessible places more accessible, distance less tyrannical, watching the world from above and always with an eye to saving precious time to meet deadlines for the next edition.

While his years in the air force as a flight instructor were fulfilling and rewarding, he was frustrated and disappointed by his commanders’ regular refusals to release him for combat duties. Men he had taught to fly were being sent to do things he wanted to do for the war effort, but like so many like-minded flight instructors his ambitions were denied.

Courtesy of The West Australian ©

Flight Lieutenant Burton’s appointment with the Royal Australian Air Force was terminated on November 14, 1945, just before his 27th birthday. However, towards the end of the war he called on James Edward Macartney, a friend and former newspaper colleague who had gone through his flight and was then managing editor of the Daily News, Perth’s now defunct afternoon newspaper.

Macartney’s invitation to join the Daily News team meant he was about to embark on perhaps the most exciting and rewarding period of his career. Macartney was a man of big vision who relished the impact of a powerful news story and understood the role the Press should play in opening up the State of Western Australia by bringing its message to a world suddenly made smaller by the just-ended World War.

Doug kept his pilot’s licence, became a member of the Royal Aero Club, and with others of the editorial and photographic staff who had also been wartime pilots, produced world-breaking news stories.

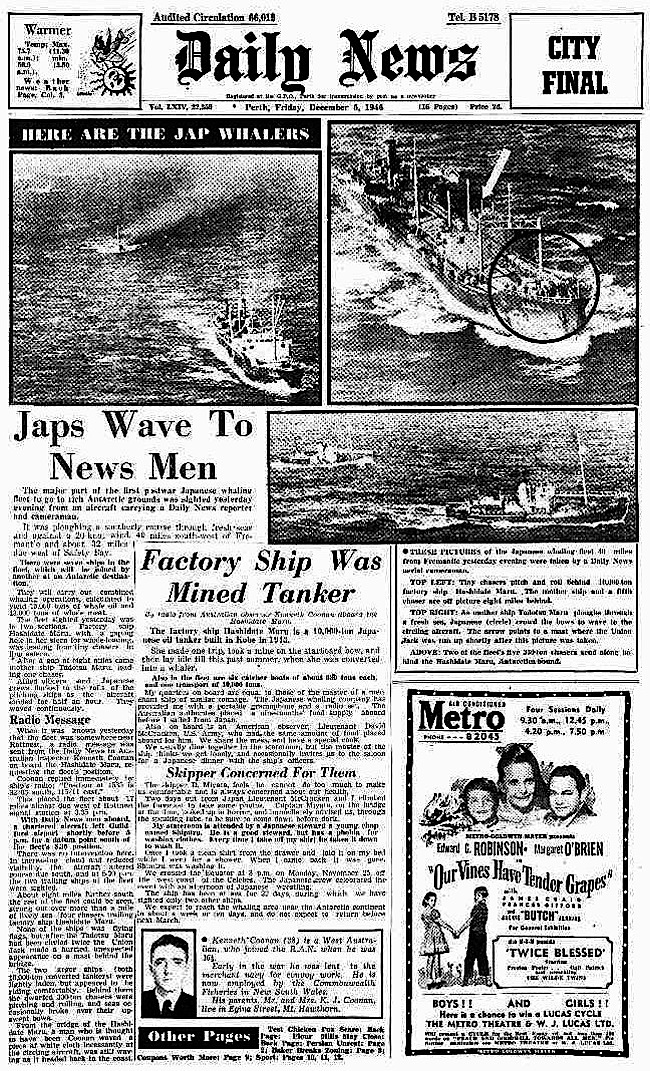

One of his more memorable assignments came shortly after the war and is as familiar today as it was 60 years ago. According to a tip-off from Canada, the first Japanese whaling fleet on its way to the Antarctic was steaming south off the WA coast with an Australian observer on board. Doug, with the Daily News’ pictorial editor, Doug Watt, chartered an aircraft to track down the ship and towards dusk, after a long flight, spotted it through a break in the clouds. They flew low, took their pictures, including one of the observer – who turned out to be a Western Australian from suburban Mt Hawthorn – and came home with a world scoop.

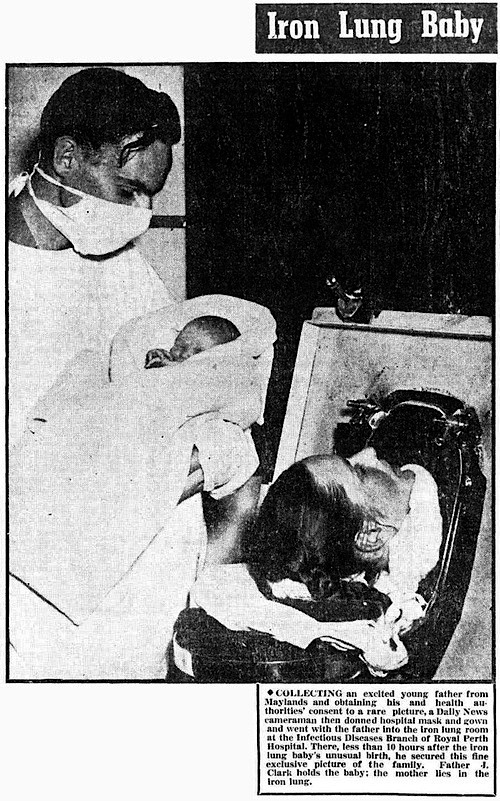

A deeply emotional assignment during the frightening 1951 polio epidemic rewarded him with achieving the picture of the year series in Britain, Europe and the USA. The photograph of a polio-afflicted mother who had given birth to a daughter in an iron lung at the Shenton Park annexe of Royal Perth Hospital resulted from gently persuading the father of the importance of such a news story and waiting two days at the hospital for the birth. Years later the child, then a mature woman, contacted Doug to thank him for sharing her story with the world.

But perhaps his greatest achievement as a news photographer was his coverage of Britain’s atomic bomb tests, the first of which was conducted on the Monte Bello islands off the north-west Australian coast in October 1952. How the story, with its extraordinary photographs, launched onto the front pages of newspapers across the world is the result of investigative journalism at its best. It is worth telling again.

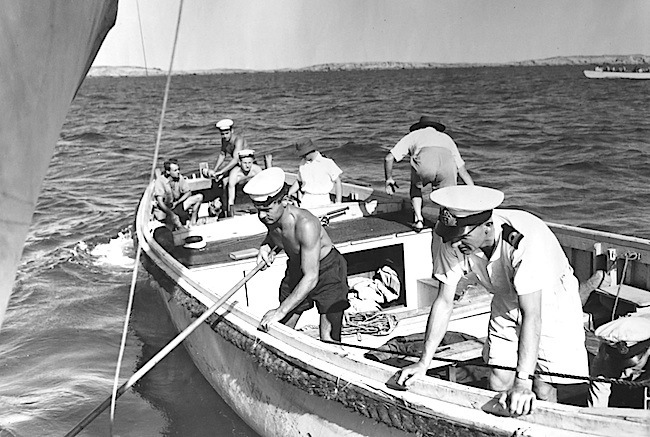

In the years following 1945 it was thought that Britain, reduced to its knees by the economic burden of two World Wars, had been left behind in the arms race between the USSR and the USA. Therefore, the disclosure in 1951 that Britain had made an atomic bomb was unexpected. The location of the test site was a strictly kept secret, though it was announced the bomb would be exploded in Australia with the expectation that the Woomera rocket range in South Australia was the most likely place. However, on April 16, 1952, two Royal Navy ships arrived at Fremantle only to slip out of the harbour a few days later. As the RN supply ships headed north the people of Western Australia learned that for two years Britain had been planning to explode the bomb on the uninhabited Monte Bello Islands, about 135 kilometres north of the nearest town of Onslow and about 70 kilometres from the WA coast.

Immediately The West Australian and Daily News learned the possible location of the test site, four men were sent to Onslow with the brief to get to the Monte Bellos, an almost impossible task when obstacles were thrust in their path at every turn. Eventually they hired a dilapidated 22-foot fishing boat to take them on the long, extremely dangerous, journey to the group of more than 100 islands. There they saw the two Royal Navy ships that had been at Fremantle a few days earlier and the islands swarming with men and their equipment . They had located the test site.

From left: Harold Rudinger, Jack Coulter, Jack Nicol and Norm Milne

Courtesy of The West Australian ©

Courtesy of The West Australian ©

Courtesy of The West Australian ©

Soon after, the Australian Government declared the islands and nearby areas off-limits, hundreds of thousands of square kilometers were restricted flying areas and other security precautions promising heavy penalties were put in place to prevent atomic spying. Adding to the heavy cloak of security and secrecy was the British Government’s announcement that representatives of the Press were banned from the area.

The only chance for The West Australian and Daily News teams to witness the atomic test was from the mainland in “rugged, barren, waterless and virtually uninhabited” country to the south of Rough Range. After long negotiations with security personnel unofficial permission was given for an observation post on the mainland outside the prohibited area. Even though it was possible the news party would see little of the explosion at such a distance and security could close the camp at any time, managing editor Jim Macartney decided to mount the expedition.

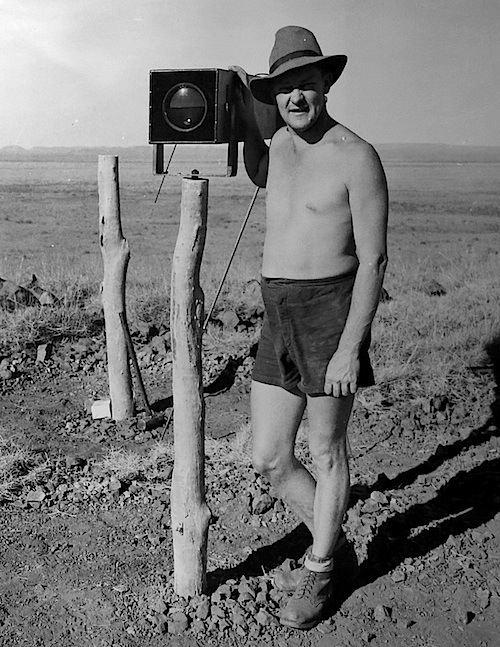

On August 16, 1952, four vehicles carrying six tonnes of equipment headed for a pre-selected site in a desolate wilderness of ironstone and spinifex 215kms north of Onslow and eight kilometres from the coast. The main camp was struck by a billabong and the observation post set up about 1.5km to the west on Mt Potter, the highest hill in the area. Because it was impossible to get a vehicle up the rocky, boulder-studded hill it took the newsmen two days to carry two tonnes of equipment to the top. Among the equipment was a camera about four metres long that had been developed and built by the scientist Bill Mangini and Doug specifically to photograph the atomic explosion. Doug believed it was the longest camera ever used on a news assignment.

Courtesy of The West Australian ©

Courtesy of The West Australian ©

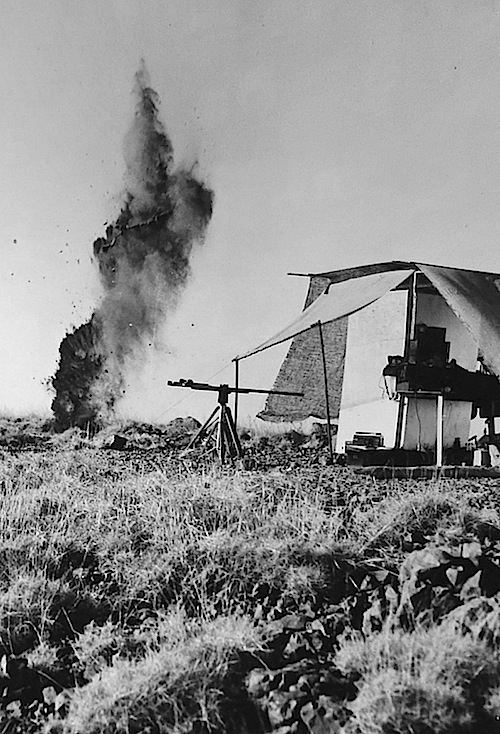

Mounting the huge cameras onto sturdy two-metre length posts cut from ghostgums growing by the billabong was exasperatingly difficult. A sledge hammer and crowbar were useless against the solid ironstone ground so dynamite was eventually used to blast the required 60cm deep holes into which the poles were sunk. By then the portable darkroom with the requisite developing dishes, enlarger and supply of film had been erected.

Courtesy of The West Australian ©

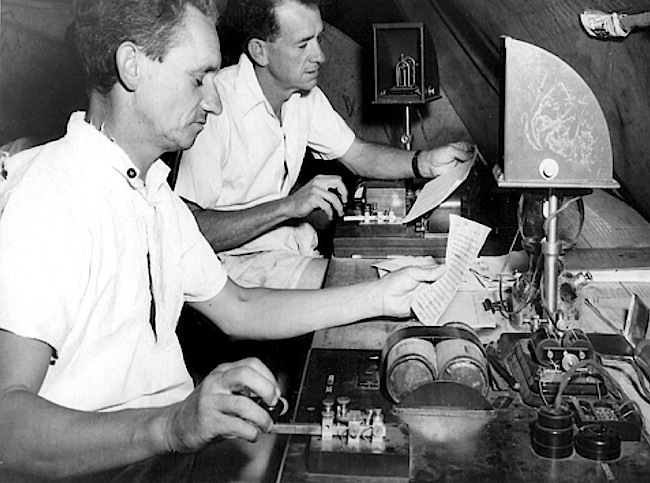

A post office was set up on the back of a truck parked at the billabong camp. A field telephone was connected between the observation hill and the post office so that reporters on the hill could telephone their stories to a copytaker on the truck, who would then pass them on to Post Master General’s telegraphists who would send the story to Perth. Such were communications in 1952.

underneath the single North-West telegraph line and staffed by

PMG telegraphists Roy (Buck) Buchanan and Ted Rodgers

Courtesy of The West Australian ©

Courtesy of The West Australian ©

Courtesy of The West Australian ©

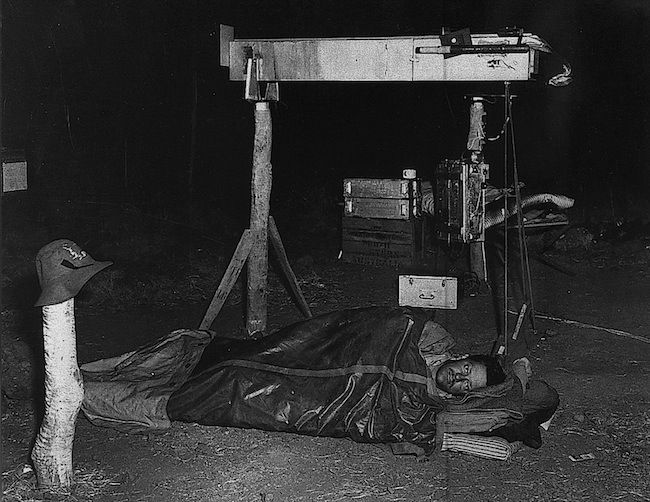

Once the camps were established and driven by the ever-present fear of equipment failure, there followed day after day of testing every camera, other equipment and the communications system in all conditions at all time of the day and night.

Then they waited, week after week, in bleak, inhospitable conditions – ceaseless winds, searing heat and flies their main enemies. The British had given no indication of the time or date of the explosion. Nor were they confident the camp would not be shut down by the authorities at any time. Each night Doug slept by his camera on the hill until Friday, October 3, when at 8am the bomb went off. In a flurry of manic activity, as the atomic cloud like an immense cauliflower appeared and grew on the horizon, the photographs were taken, developed in the tiny darkroom, the film put into billy cans and rushed down the hill to be driven to a chartered aircraft ready at Mardie Station landing strip and flown to Perth. More negatives were sent by road to Onslow to be air-lifted to Perth. Everything went to plan. Doug’s first picture of the explosion was used in countless publications around the world.

Courtesy of The West Australian ©

Considering this was a time of unsophisticated wired communications and long before rapid-fire digital photography, no less than 175 photographs were taken in the first four minutes of the explosion and another 65 in the following three minutes. The first news flash reached the newspapers’ Perth offices 75 seconds before the bomb’s sound wave reached the Mt Potter observation post almost 100 kilometres from the test site.

Courtesy of The West Australian ©

Courtesy of The West Australian ©

Jan Burton Jackson’s account continues in Part 3.